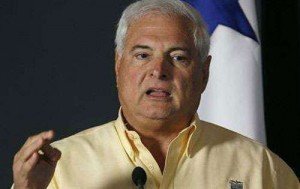

(Eurasia.com) Panama’s booming economy and newly acquired investment grade status have made the tiny tropical country a market darling. A number of factors, including a slew of corporate tax incentives, the government’s efforts to get Panama off the OECD’s grey list of tax havens, and the ongoing expansion of the Panama Canal, have enticed investors over the past few years, and the World Economic Forum just bumped up Panama’s competitiveness ranking. But beneath the glittering veneer of economic progress lies reason for skepticism: President Ricardo Martinelli’s recent antics.

A conservative supermarket chain owner and the leader of the right-of-center Democratic Change party (CD), Martinelli promised to “build a government of national unity” when he won the 2009 election. Since then, however, Martinelli has engineered a series of defections from rival parties in congress, raising the number of CD representatives and bringing him tantalizingly close to the 36-member majority that would free him from having to forge alliances. And while Martinelli has followed through on promises to boost pensions and ease transportation bottlenecks in Panama City, the self-proclaimed “loco” leader has also proven to be brash and mercurial.

On Aug. 30, Martinelli issued a terse press release relieving the Panameñista vice-president, Juan Carlos Varela, from his duties as foreign minister. The spark was a seemingly innocuous reform proposal: to introduce a second-round run-off in the presidential election. But many politicians felt that Martinelli’s motivation was less about reform and more about keeping his party in power in 2014, when his term ends. The opposition Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) has the most support nationwide (when measured by the number of registered voters), and the CD and the Panameñistas made a pact to join forces for the 2009 and 2014 elections to avoid splitting the conservative vote. A potential second-round run-off has already emboldened the CD to ditch the pact and run its own candidate in 2014. The party figures that it has a good chance of finishing second to the PRD candidate in the first round and winning with the full conservative vote in the second.

These calculations were clear to the Panameñistas, who balked at letting the reform through the assembly, demanding instead that Martinelli get it approved via a public referendum. In response, the president simply sacked Varela and forced other Panameñistas out of government. An unrepentant Martinelli then tweeted that “politics is the art of making false friends and true enemies,” and relations between the formerly allied parties have only grown more contentious. The president has been accused of attempting to blackmail Panameñista leaders and participating in corrupt land deals, while senior Panameñistas formerly in the administration report that they have been prevented from accessing their offices and computer files.

In the face of such turmoil, it’s unclear how much Martinelli will benefit from his determination. Sure, he now has the numbers in congress to push through his reform. But a host of spurned Panameñistas are looking for payback, and opposition parties are threatening to fight the reform both in court and on the street. Martinelli said this week that he would put the reform to a public referendum in 2012, even if it passes the assembly, but his popularity has taken a hit and voters are unconvinced by his proposal. A recent poll found that the president’s approval rating fell 20 percentage points in the past month, and that nearly 80 percent of the country’s voters are not in favor of a second round. Together, the crumbling of Martinelli’s governing alliance, the sharp drop in public support, and the uphill battle to pass the electoral reform suggest that policymaking could continue to be turbulent for the remainder of Martinelli’s term.

Heather Berkman and Adam Siegel are part of Eurasia Group’s Latin America practice.