(Al Jazeera) The border between Panama and Colombia is perplexingly unique.

(Al Jazeera) The border between Panama and Colombia is perplexingly unique.

It’s the meeting point of two countries and two continents – North and South America – with long, connected histories of trade and migration.

Yet it’s one of the only international frontiers without a pliable road across it. The 225km boundary, stretching from the Caribbean coast through dense mountainous jungle and swamps to the Pacific Ocean, has no formal crossings for people or cargo.

Foreigners require prior permission from Senafront – Panama’s border police – to access the neighbouring province of Darién, and any visitor must navigate numerous security checkpoints heading in and out.

People still traverse the frontier: smugglers, paramilitaries, undocumented migrants, as well as indigenous people who call the region home. Its remote nature and chronic insecurity suits many of their needs.

Increasing numbers of undocumented migrants, from as far away as South Asia and Africa, are traversing through the region. They arrive in South American countries and risk their lives on this perilous path, invariably headed to the United States.

The movement of drugs, rebels, and North America-bound migrants is stretching the resources of Darién – and residents’ patience.

“The people are trying to build a wall against these pressures,” said Ivan Lay, 64, the provincial director in Panama’s interior ministry, through a translator. “But the avalanche is powerful.”

Blessing and a curse

The Spanish conquistadors who arrived here in the 16th century named the area the Darién Plug – Tapón del Darién – for its impassibility.

Today, outsiders call it the Darién Gap: the only interruption in the Pan-American Highway, a 48,000km network of roads stretching from Alaska to Argentina. The highway ends in Yaviza and restarts on Colombia’s northern coast.

Its wild character was once an asset. The lightly populated, dense jungles and swamps kept most trade and migration to the coasts. This helped preserve diverse wildlife, rainforest, and traditions of indigenous people – such as the Guna, Embera and Wounaan – who straddle the border.

But remoteness and weak central authority have become a liability as armed groups such as the FARC and later traffickers arrived from Colombia.

“The threats are totally unveiled,” said Edilfonso Ají, 41, a regional Embera chief, through a translator. “Fear is constant.”

Senafront is the state institution with the greatest presence in Darién because Panama is “an obligatory stop” for migrants and US-bound drugs, said Commissioner Yadel Cruz, the second in command. Traffickers use land, air and, increasingly, ocean routes. About 2,000kg of narcotics was seized in a single haul near the Caribbean coast in March, said Cruz.

Men are typically paid about $500 to traverse the jungle with rudimentary backpacks made of vines containing up to 20kg of cocaine, said Commissioner Abdiel Lezcano of Senafront. Horses saddled with hundreds of kilos have even been sent unmanned over the border, he said.

Once drugs reach Yaviza or other points on the Pan-American Highway, they are hidden above, below and inside vehicles, in everything from gas tanks to panelling, Cruz said.

“Sometimes we are surprised by how sophisticated they are,” he said. “The narcos have a lot of time to think and are very creative.”

Senafront collaborates closely with neighbouring Colombia. “They have been a huge help in trying to deal with those issues,” explained Cruz. He declined to discuss any US role in the region.

The US embassy did not respond to a request for comment.

The commanders recalled Colombian intelligence alerting them that all the men in a coastal village had disappeared overnight. Panama’s navy intercepted the group of about 50 empty-handed on their return journey, suspected of having completed a drug run.

They said Senafront recognises security measures alone cannot solve the problem and educates young people about the perils of joining the narcotics trade. “We try to awaken the conscience of people, that they are the victims of this but also part of the solution,” Cruz said.

Indigenous impact

The pervasive insecurity of the past two decades and growing demand for natural resources – from hydro-power and timber, to land for growing agricultural products and transport – have altered many aspects of life here, especially for indigenous groups.

Leonardo Mepaquito, an official from the indigenous Wounaan community of about 3,000 people, said paramilitary groups have used violence against them, while narco-traffickers try to recruit young people.

“Our people have been traumatised,” Mepaquito said.

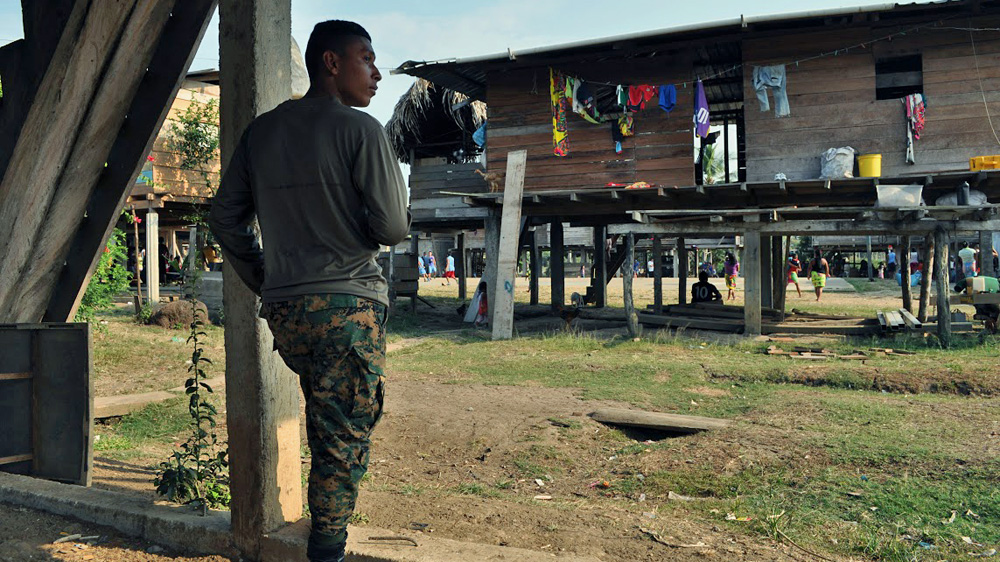

Embera people are similarly uneasy walking jungle paths at night and live in bigger villages for protection, explained Viseida Guaynora, 35, chief of Marragantí in Comarca Embera-Wounaan, a semi-autonomous territory.

“The natural way of the Embera is not living in such big groups,” she said. “Definitely it’s a problem to live so near to the border.”

Edilberto Dogirama, president of the Embera-Wounaan General Congress, representing 41 regional communities, said the increased presence of Senafront had caused its own problems. Tensions spiked over restrictive rules governing the movement of goods and heightened concerns their constitutional rights to autonomy were being eroded in the name of security, he explained.

Dogirama said the low point came from 2005-2008, but more indigenous were now joining Senafront’s ranks and their policies had loosened. “What you see today is a huge improvement,” he said, noting security was better too. “A decade ago, the danger from guerrillas was much higher.”

However, the state’s presence remains minimal and indigenous leaders said they feel abandoned in healthcare and industry.

Through collaboration with NGOs, Marragantí created a sustainable timber export venture with a Chinese company. In its first year, the business generated $80,000 that went to improving 98 of the village’s houses, according to Francisco Guainora, leader of the operation.

“We’re not waiting for help from the government,” he said.

End of the road

Despite Yaviza’s distance from the border – a two-three day, 80km journey by boat and foot, depending on the season – it has the feel of a frontier town.

Ramshackle wooden homes on stilts rise above dirt and trash. Hawkers sell cheap goods at makeshift stalls on narrow dusty streets; men nearby drink beer amid blaring music mid-morning.

Long dugout canoes weighed down by plantains and other local produce dock at the port. Situated at the meeting point of two rivers, it’s a historical hub of about 4,000 inhabitants – the majority of Colombian origin, part of past migrations from nearby Chocó province.

Leticia Pitti Lewis, 62, a former mayor who arrived in Yaviza aged 18 to teach, said through an interpreter that the town has an independent spirit. She recalled an infamous incident in the 1980s, during the rule of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, when some of the town’s men were banished to the border for 15 months after celebrating Colombia’s July 20 Independence Day with a parade.

Lewis noted much had changed. “When I came here there was nothing: no electricity, no running water, no services, transport only by river.”

In the 1970s the Inter-American Development Bank funded an ambitious development plan for the region, which included construction of the Pan-American Highway to the Colombian border. That was never completed. The road as far as Yaviza has slowly been upgraded, at the gradual expense of its isolated character.

Lay, the province director, said the town now has two university campuses, schools to 7th grade and 15 churches. But he conceded narco-traffickers take advantage of the persistent poverty. “We are easy prey.”

For Lewis, Yaviza was unprepared for the impact of the road: young people left for the capital; newcomers arrived seeking land; worst of all, it opened the door to traffickers.

“This place has been totally saturated and contaminated by the drug trade,” she said. “The only thing they haven’t done is put the drugs on the shelves in public.”

“I don’t see a future for this place,” Lewis added. “Before they removed the Darién’s plug, life here was healthy.”