(Miami Herald) They sit there motionless atop the horizon, ships of global commerce in perpetual line. Cloud-slung skies silhouette their bulk as crewmen bide the hours and days, impatient in the wet tropical heat for their turn to enter this grand gateway of the world — the Panama Canal.

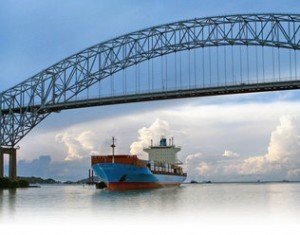

We wait too, bobbing beneath the arching iron of the Bridge of the Americas, wondering which of the darting tugs will deign to slot our humble 60-foot cruiser into the first set of locks on a 50-mile, best-part-of-a-day journey between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Size evidently matters. Three vast container carriers have already sloughed by, gifting us with lumpy swells and causing not a few on board to question their enthusiasm for the hearty on-board breakfast. A day sipping rum-and-something poolside at the elegant El Panama might have been a more comfortable choice, but it would hardly have satisfied my boyish enthusiasm for things engineered.

Building a marvel

As human constructions go, it doesn’t get any better than this. The Panama Canal was the climax of an age of confidence and can-do. The late 19th century had seen the Atlantic Cable laid, the Brooklyn Bridge built, and the Wright Brothers experiment with manned flight. People were reading Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea and watching moving images on Thomas Edison’s new-fangled Kinetescope. It was a time when nothing was impossible, least of all for Ferdinand de Lesseps, the genius of Suez, who was first to put shovel to the long-held dream of forging a path between the two great oceans. And so he strode into one of the wildest, least-known corners of the world, only to find that unforgiving geography, merciless disease and questionable financing would put pay to his second chance at glory.

It took President Teddy Roosevelt and the straight-jawed efficiency of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to step up to the task. And step up they did, a full 85 feet from sea level, and down again, in a massive lock and lake construction that today, just three years shy of its centennial, continues to amaze in the way it defies nature.

You can get a fine view of the canal from the deck of a transiting cruise liner, but there’s nothing quite like getting up close and personal in a smaller craft, touching the algae-covered concrete walls, listening to the creak of the massive iron lock gates, and feeling the power of millions of gallons of water bubbling in and gurgling out as you are first raised up, then settled down in an effortless crossing of the Central American cordillera. In this place, perspective is everything.

We are just three dozen or so tourists, on a lovingly-restored wooden craft designed for 105, the lean complement no doubt due to the ungodly hour — 7:30 am. — she slips Balboa quay for her monthly full transit, which takes about seven hours. Patrick, the Panama-born American tour guide, keeps us attentive during all the sloshing around with mind-boggling facts and figures about annual transit tonnage and passage fees (a whopping $200,000 for the biggest container ships) and other FAQs (the Pacific to the Atlantic may seem to be an west-east journey, but the Canal is actually built north-south). And by the time the tug Esperanza finally beckons us on to the first set of gaping locks at Miraflores, and into a cozy corner astern of the Chinese bulk freighter Khang Zong, we are eager for the show to begin.

In an instant the surface water in the 1,000-by-100-foot lock chamber starts to churn, only there is no appreciable sound; just a sensation of rising ever so slowly in a silent elevator. With the steep, endless walls slowly receding beneath caramel-colored waters, the blue, cotton-clad sky broadens. And high up on the rim, a distant figure of a dockside lineman now acquires face and features.

As the water in the first chamber reaches the same height as the water in the one ahead, the intervening gates open and the electric whir of the dockside locomotives sound as the Khang Zong is slowly towed onward (container carriers do not use their own power in the locks). We follow, snuggling in behind the massive ship, and as the gates close behind us the process begins all over again. Over the loudspeaker Patrick informs us that five million sacks of cement were imported from the United States to build the six sets of locks at Panama, but I can only think about the stark simplicity of it all.

While de Lesseps had clung to the impossible notion of building a sea-level canal as he did at Suez, the plan conceived by TR and his engineers was to rise up on a liquid “staircase” to a massive man-made lake, then drop back down the same way at the other end. It was nothing less than pure genius.

As the tropical sun begins to prickle, we complete the passage through the first three locks — two at Miraflores, one at Pedro Miguel — and arrive at the canal’s full height of 85 feet. above sea level. From here we push into the Gaillard Cut, an enormous ditch eight miles long and 500 feet wide that slices through the spine of the cordillera. The summit of Culebra that once stood here was an obstacle even TR and his brilliant engineers couldn’t rise above. Imported Caribbean workers had to dig and blast their way through. And they died in droves; from malaria and yellow fever, and from their own sticks of dynamite; in all, as many as 500 workers died for each mile of the canal.

Into the jungle

But Patrick doesn’t do doom and gloom. As we cruise past Gamboa and pick up speed toward Gatun Lake, his commentary moves on to the wondrous things being done in the study of tropical flora and fauna at the Smithsonian Institute facility on the rapidly-approaching Barro Colorado Island. This lush green oasis is all that is left of what was a contiguous piece of jungle with thriving communities — Barbacoas, Tabernilla, Frijoles, Bohío Soldado — that now lay beneath us at the bottom of the world’s largest man-made inland lake. On the lake’s glistening surface Esperanza, our chaperone, now breaks loose like a house-bound terrier set free in the park.

Beer and cold cuts are broken out for lunch. Binoculars pass between those with an eye for the magnificent tropical birdlife. As the jungle encroaches, the sun beats down, and the lake waters lap at our wooden hull. And with a promise from Patrick to wake me at Gatun Dam, I find a sturdy wooden deckchair and snooze.

Of the many challenges faced by canal engineers, none was greater than taming the mighty Chagres River. During the years of construction, this languid artery in the dry season became a fearsome torrent in the wet, roiling through the isthmus, destroying everything in its path. De Lesseps’ efforts never got far enough to face the problem head on, but for TR’s men it was occasion for another bold solution.

Gatun Dam towers up from the jungle on the western shore of the lake and was once the world’s largest earthen dam. It remains the keystone of the entire workings of the Canal, channeling the power of the mighty Chagres to feed the locks and contain the water. The dam’s importance to the project was famously illustrated by Panamanian strongman Gen. Omar Torrijos who, during the tough negotiations for the return of the sovereignty of the canal, once casually said: “Blow a hole in Gatun Dam and the canal will drain into the Atlantic. It would take only a few days to mend the dam, but it would take three years of rain to fill the canal.”

At Gatun Locks, where the canal makes its final three-stage descent back to sea level, quiet jungle gives way to yawning cranes, thrumming dredges and the cacophony of clearing and grubbing that now accompany the first serious construction here in almost 100 years. Under the presidency of Torrijos the son, the Panama Canal is undergoing a massive new expansion to meet the demands of growing 21st century commerce. New lock chambers, longer, wider and deeper, are being built parallel to the old in order to double traffic and cater to today’s larger post-Panamax ships.

Yet despite the march of progress, the Panama Canal will remain a monument to the derring-do of a century ago. As we debark at Cristobal on Panama’s Atlantic coast, I think only of the wily visionaries, de Lesseps and Teddy Roosevelt; of the brilliant engineers, Stevens and Goethals and Gaillard; of William Gorgas and the tireless doctors whose taming of deadly disease made the project possible; and of the thousands of nameless laborers, like the great-grandfather of the Barbadian taxi driver into whose cab I now climb, whose labors put shape to one of Man’s greatest dreams.

Tropical night comes quickly as Winston the cabby drops me at the Spanish mission-style Hotel Washington in nearby Colon. Above the grand portico, I see the same painted plaster emblem under which generations of canal engineers have passed; of a galleon under full sail transiting the steep Gaillard Cut, with the legend: “The Land Divided, the World United.” It is an apt sentiment of those extraordinary times, when anything was possible, when no price was too high, no promise left unfulfilled. Rain begins to spatter the hotel terrace as I gaze out on Manzillo Bay and see the twinkling navigation lights of container carriers in their never-ending line, waiting their turn to take their own historic journey, slowly down the wonder.